Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP): Definition, Variants, and Real-World Examples

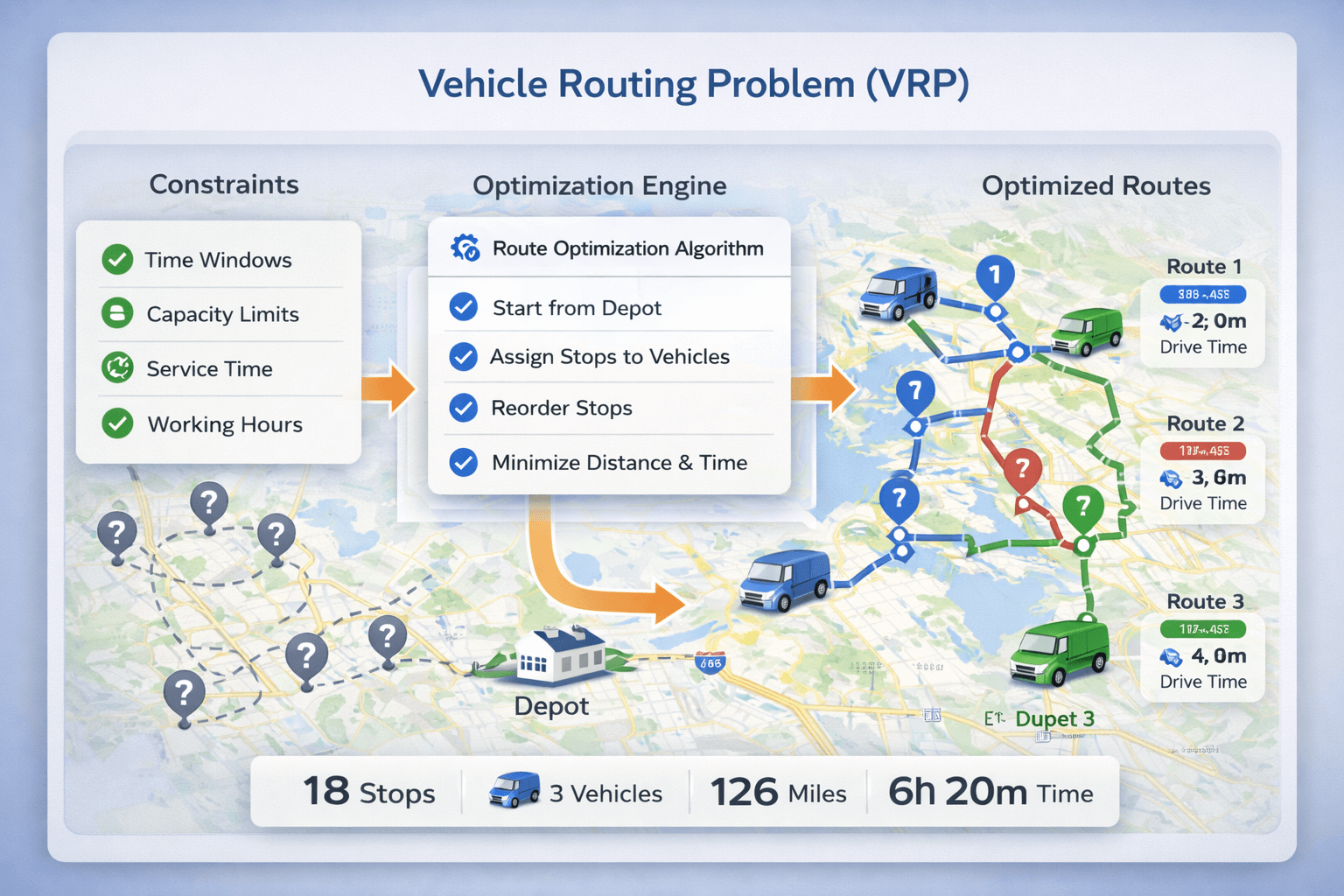

Quick definition: The Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP) is the task of

assigning many stops to one or more vehicles and ordering each route to minimize cost (usually time or distance),

while respecting constraints like time windows, capacity, service time,

and driver working hours.

VRP = assign stops to vehicles + choose stop order under constraints (the core of route optimization).

VRP = assign stops to vehicles + choose stop order under constraints (the core of route optimization).

What is the Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP)?#

VRP is the general “fleet routing” problem behind delivery routing, field service scheduling, and multi-driver route planning.

It asks: how do you build one or more routes that visit all required stops efficiently?

In practical terms, VRP means deciding:

- Which vehicle should serve each stop

- In what order each vehicle should visit its assigned stops

- When each stop should be visited (ETAs), while staying within constraints

This is exactly what route optimization software does.

If you want the practical overview, start with the pillar:

Route Optimization: Complete Guide.

VRP vs TSP: what’s the difference?#

A common confusion is VRP vs the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP).

- TSP: one vehicle must visit all stops once and return (or end) — “best single tour.”

- VRP: multiple vehicles may exist, stops must be assigned to vehicles, and constraints are common (time windows, capacity, working hours).

In other words: VRP is “TSP for the real world.”

Why VRP is difficult#

VRP becomes hard quickly because the number of possible solutions explodes:

you’re not only choosing an order of stops, you’re also choosing which vehicle serves which stops.

Add constraints like time windows and capacity and many candidate routes become invalid.

That’s why production route optimizers focus on high-quality solutions quickly, not perfect optimality.

Common VRP variants (types you’ll see in practice)#

Most “route optimization” problems are one of these VRP variants (or a combination).

Table of common Vehicle Routing Problem variants and what they mean

| Variant |

Meaning |

Real-world example |

| VRPTW |

VRP with Time Windows (must arrive within allowed time range) |

Deliveries with appointment windows (9:00–12:00) |

| CVRP |

Capacitated VRP (vehicle has weight/volume limits) |

Truck payload limits, van capacity planning |

| MDVRP |

Multi-Depot VRP (vehicles start from different depots) |

Regional branches / hubs |

| SDVRP |

Split Delivery VRP (a stop can be served by more than one vehicle) |

Large orders split across trucks |

| PDVRP |

Pickup and Delivery VRP (pickup must happen before drop-off) |

Courier pickups + deliveries |

| Open VRP |

Routes do not need to return to depot |

One-way routes ending at driver home/base |

| Backhauls |

Deliver outbound, then pick up inbound loads |

Delivery + returns collection |

If your business operates on appointment windows, see:

Route Optimization with Time Windows.

If you use multiple drivers, see:

Route Optimization with Multiple Vehicles.

Real-world constraints VRP models support#

In real operations, the “shortest route” is often not feasible. Constraints define what’s allowed.

- Time windows: arrive only during customer availability

- Service time: time spent at each stop (delivery, inspection, paperwork)

- Vehicle capacity: weight/volume limits and stop demand

- Working hours: shift start/end for each vehicle/driver

- Start/end locations: depot, warehouse, or driver home base

- Priorities: urgent stops first or guaranteed delivery rules

This is why “stop reordering” is not the same as optimization for fleets.

For the practical workflow, read:

How route optimization works.

How VRP is solved in practice (without heavy math)#

Large VRP instances are rarely solved by brute force. Instead, route optimization engines typically:

- Build an initial solution quickly (a feasible route plan)

- Improve it iteratively by swapping stops, moving stops between routes, and re-ordering sequences

- Balance speed vs quality to return results fast enough for daily dispatching

Practical takeaway: the best routing tools focus on feasible routes that drivers can execute —

not just “shortest distance.”

If you want the business outcome side, see:

Route optimization benefits.

What data you need to solve VRP#

To get accurate routes and ETAs, you need good inputs. Here’s the minimum checklist:

Stops

- Address or latitude/longitude

- Optional: service time (minutes at stop)

- Optional: time windows (earliest/latest)

- Optional: demand (weight/volume)

Vehicles / drivers

- Start location (and optional end location)

- Working hours (Time In / Time Out)

- Optional: capacity limits

TrackRoad supports these inputs (including Excel import) here:

Route Optimizer.

Simple VRP example#

Imagine 30 delivery stops and 3 vehicles.

The optimizer must decide which stops go to which vehicle, then order the stops on each route to minimize travel time,

while ensuring each driver finishes within working hours and time windows are met.

That combined “assignment + ordering + constraints” is VRP — and it’s why route optimization is more than navigation.

FAQ#

What is the most common VRP type in delivery?

VRPTW (time windows) and CVRP (capacity) are the most common in delivery and field service routing.

What does VRPTW stand for?

VRPTW means Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows — each stop must be visited within an allowed time range.

Can VRP include multiple vehicles and depots?

Yes. Many real fleets are multi-vehicle and often multi-depot (MDVRP) depending on how operations are structured.

Is VRP the same as “stop optimization”?

Not really. Stop reordering is a small piece. VRP usually includes assigning stops to vehicles and respecting constraints like time windows, capacity, service time, and working hours.

What’s the best starting point if I’m new?